Context & Origins

The “World Builder” project was a broad reimagining of iR Studio, which initially consisted of a 3D engine and editor developed by Ethereal Engine, acquired by Infinite Reality. EE's vision for the product was general purpose or social; iR's target market for the product was more tightly focused on small e-commerce businesses. This led to an incremental program of UX improvements nudging the Editor away from a web-based Unity competitor to something more accessible, which I explain in detail in that case study [1].

Near the 1.0 general availability launch of iR Studio, leadership recognized the disconnect between the expectations of their customer base and the complexity of the Editor tool. The team quickly bolted on a “wizard” onboarding, but splitting resources at that late stage resulted in two disparate product surfaces that both fell short. Presenting customers with two extremes—an intimidating Editor and overly-simplistic Setup Assistant—did allow us to collect a lot of very helpful feedback from beta users. Another pivot after launch let my team focus fully on taking these insights into the successor.

Starting at the End

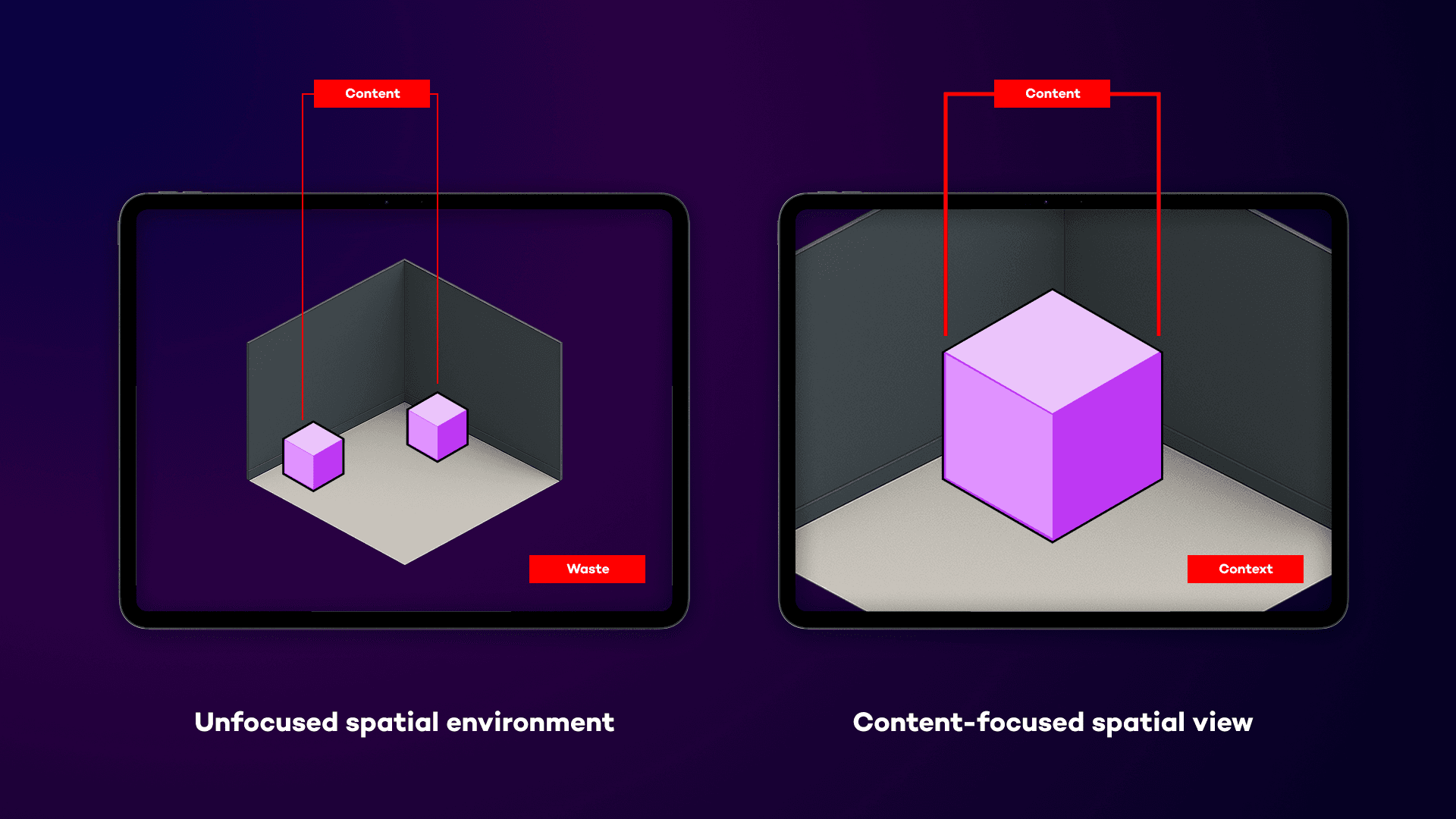

That early feedback made it clear that templated designs were a dead end. The most validating (and damning) evidence of this was in the data: customers overwhelmingly abandoned the product at the first step where we showed templates. It may seem counterintuitive to suggest that offering simpler solutions would decrease acceptance, so consider why templates work so well on standard webpage builders, desktop publishing and blogs: colors, images, font choices, branding—content, generally—completely change how the site looks and what it does.

In a spatial environment, customer content is comparatively minuscule; an overwhelming percentage of the screen is taken up by immutable virtual architecture [2]. On top of that, the space is finite, demanding a precise amount of content; too little and it feels incomplete, too much and it won't all fit. Effectively, every site published with our Setup Assistant was identical and required customers to need exactly what we had provided.

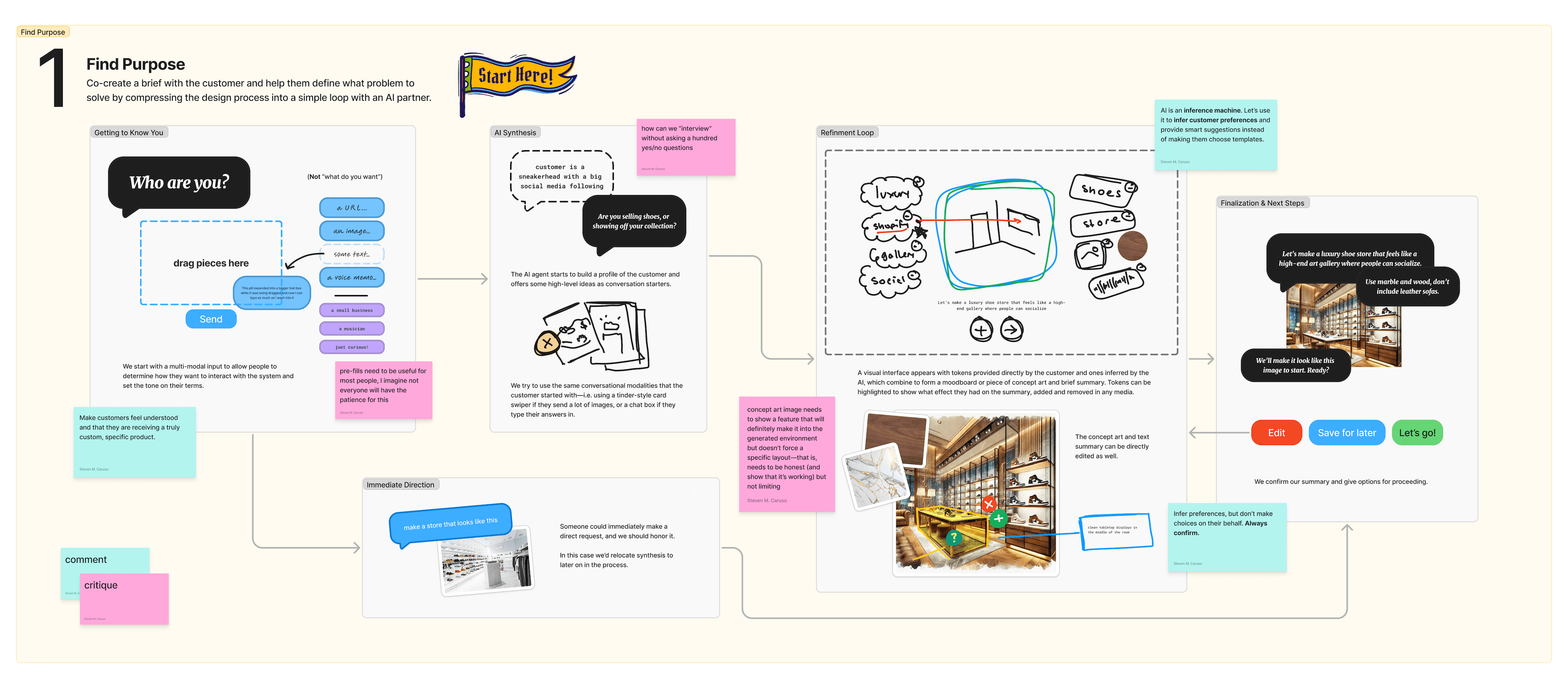

This realization led directly to the first major inversion of World Builder: customer content drives everything else. By orienting the onboarding flow around multi-modal interaction with an AI agent, we would collect or infer as much intention and source material from the customer as possible, and then work with them to build something to best support it.

Reimagining World Structure

To make the creation process intuitive, we needed a new vocabulary that was both precise and easy to grasp. We borrowed terminology from theater and film productions to organize Worlds—technical in its way, but also a big enough part of culture for understanding to be universal, if cursory.

| Term | General Meaning | Studio Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Buildout | improvements or modifications made to a space | customizations made to the Structure of a Set |

| Collection | an ordered grouping of items | a defined group of Content and/or Set Pieces derived from an existing Set or used to create and fill a new one |

| Content | information in a website or other medium | all-inclusive term for objects and information that can appear as Set Pieces or be presented by an interaction with them |

| Kit | a set of parts or tools relating to a common task | Props and Structure conforming to a Template's Style |

| Project | a planned body of work sharing a common goal | a workspace containing Spaces and Content that are aware of one another and possibly connected together |

| Prop | a movable (nonstructural) object on the set of a play or movie that actors can interact with | a kind of Set Piece that is non-structural |

| Role | the function performed by a person or thing in a given situation | a status of a Set Piece giving it certain behaviors and interactivity |

| Scene | a sequence of continuous action; events that occur on a set | a specified view of a Set with specific Roles associated with Set Pieces on the Set |

| Set | a group of things that belong together, used together in a scene | a discrete collection of objects including Structure and Set Pieces assembled into a unit |

| Kit Piece | a part of a set, including structures and props | an object that is placed in or is part of a Set |

| World | an unoccupied area rented as a place of business | the area inclusive of all Sets in a project that can be published |

| Structure | a building or other thing assembled from many parts | the underlying geometry and Style of a Set that can be modified with a Buildout and provides a boundary that can be populated with Set Pieces |

| Style | a distinctive appearance aligning to a greater theme | specific materials and visual themes that a Template's Kit conform to |

| Theme | a preset format that can be copied to create new items in a similar style | a container for Styles and Kits that determine default settings and suggested Buildouts and Set Pieces |

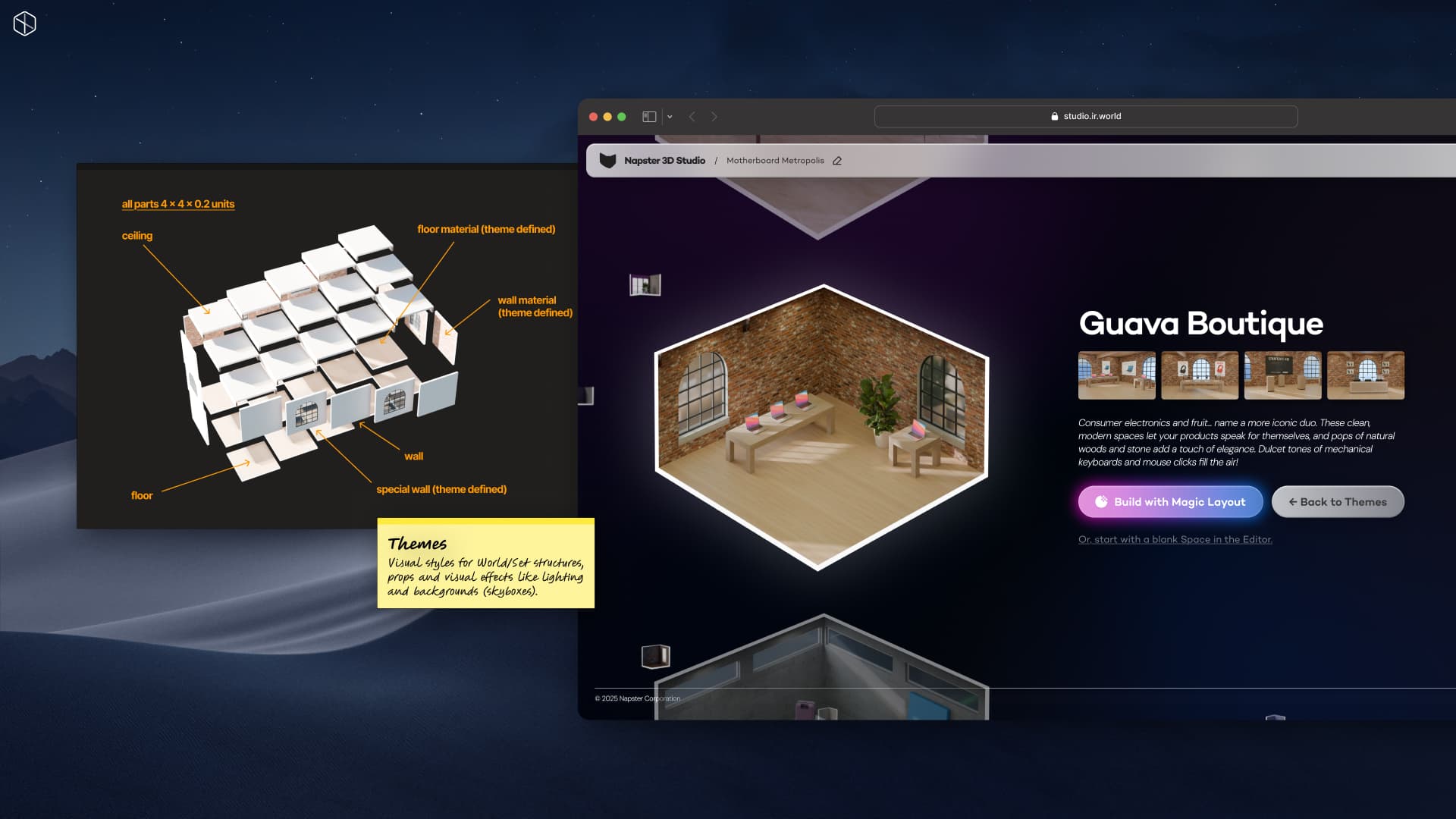

The basic unit of structure would be Sets: generalized assemblies of 3D objects, including structural elements, backgrounds, decorative props, and content that formed the basis of what's shown on screen once published.

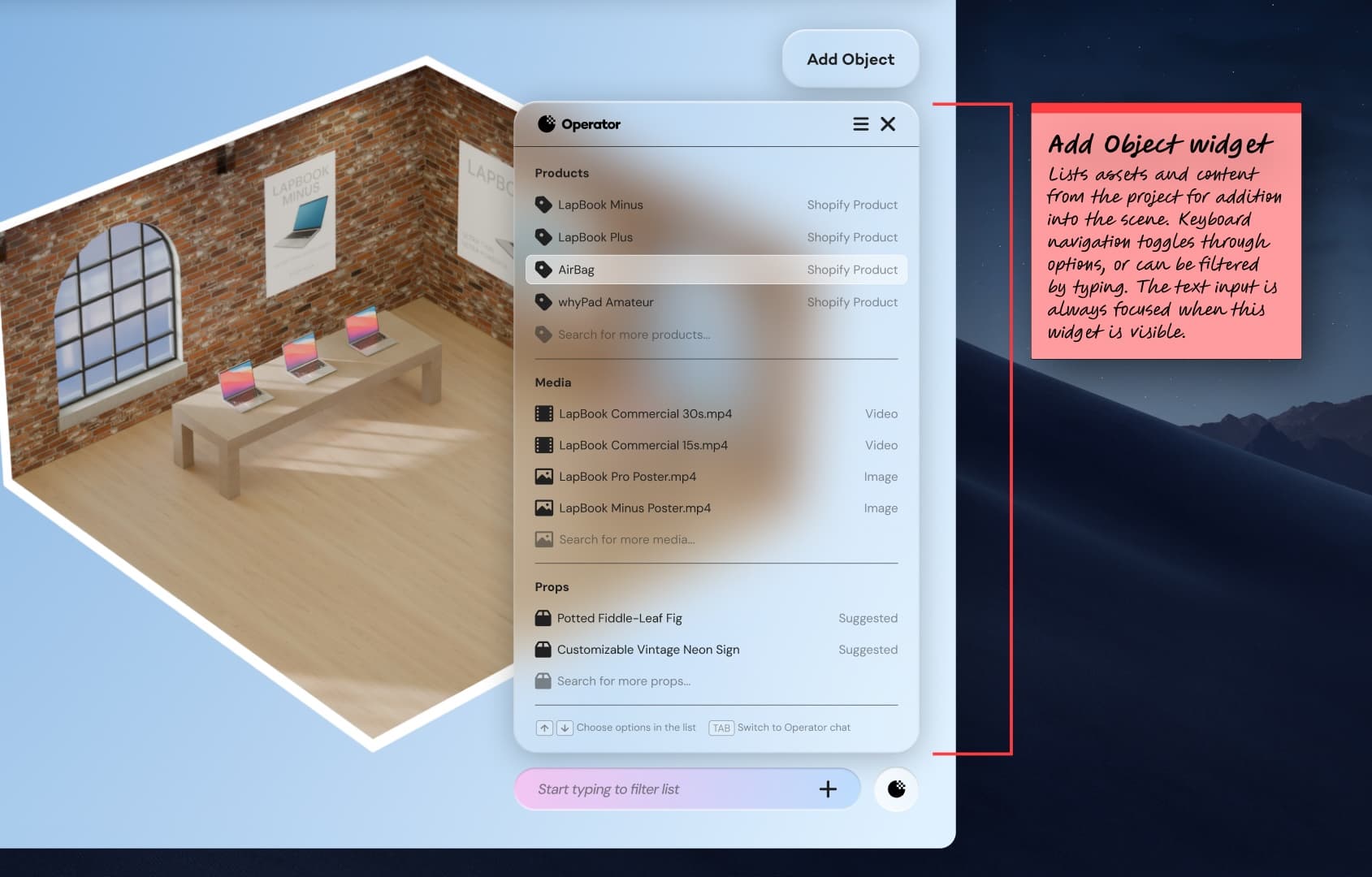

Those objects, Set Pieces, are assigned a Role that justifies their presence. Products and Media, for example, are interactive and come with specific behaviors. Props and set structure are purely visual. Roles map to predefined compositions in the Engine's entity-component system (ECS), now abstracted away completely.

Everything in our asset library would be crafted to align to cohesive Themes, interchangeable visual styles (materials, colors, lighting) that are decoupled from function. While they could be mixed-and-matched, the structure of our human-selected kits would give the AI agent confidence to make good choices when assembling Sets around customer content.

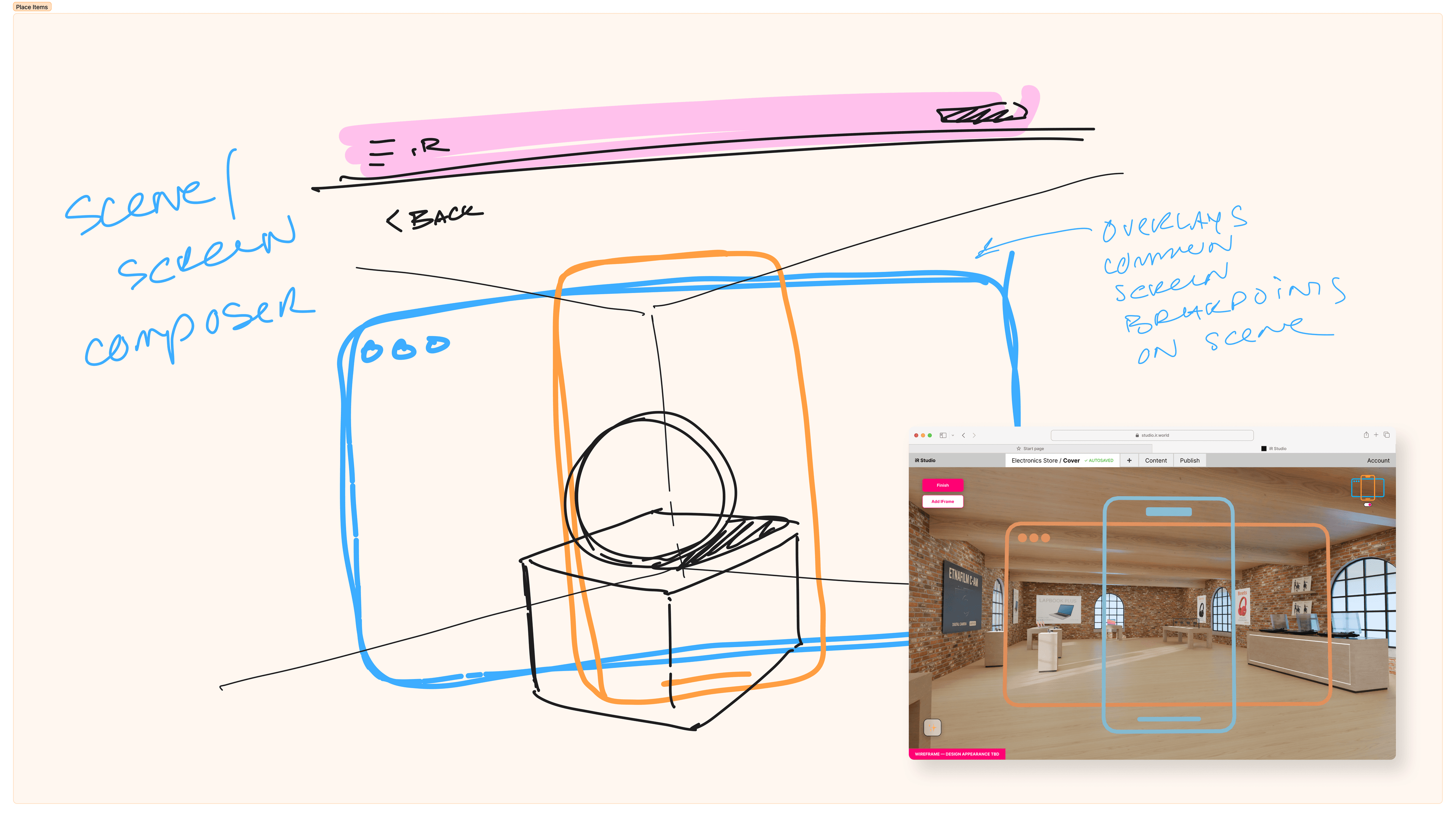

Finally, Scenes were defined as the action that happens on Sets, where the Set Pieces all play their Roles to tell the story of customer content. Scenes are also the navigational unit of Worlds, acting as keyframes for camera movements and giving customers and the Engine tighter control over what's shown on screen.

This was the next major inversion from iR Studio—we'd no longer use first- or third-person avatars and WASD keyboard control to navigate, but treat Scenes as individual pages on a site or slides in a deck to be moved between with menus, scrolling, and hyperlinking. Reorienting around a more familiar interaction model was crucial for user acceptance; a huge number of users in testing didn't even know they could change the view, and would be terminally confused by any accidental movement.

Immersive Navigation & Embeddable Worlds

We've sorted out how to build interactive 3D worlds and publish them to the web, but there's still an outstanding question of why. User data and ethnographic research showed clear challenges here: it wasn't obvious to customers how these experiences were better than their preexisting e-commerce solutions, and it demanded a kind of creative asset that most of them couldn't provide.

Our target customers were “Main Street” retailers and service sellers; immersive experiences require high-quality, optimized and performant 3D models of products. Only big enterprises and manufacturers typically have these—and they're unlikely to be using a tool like ours to make an immersive web experience; they'd hire an agency to do it. So our customers either have what their suppliers give them, or have to make it with limited resources and almost no specific technical knowledge. Filling a Shopify or Squarespace site with product details and appealing photos is already a major undertaking, but there's a clear return on investment in the form of e-commerce sales. Replacing a simple site that works well with a complicated one that end users find challenging to navigate is a nonstarter.

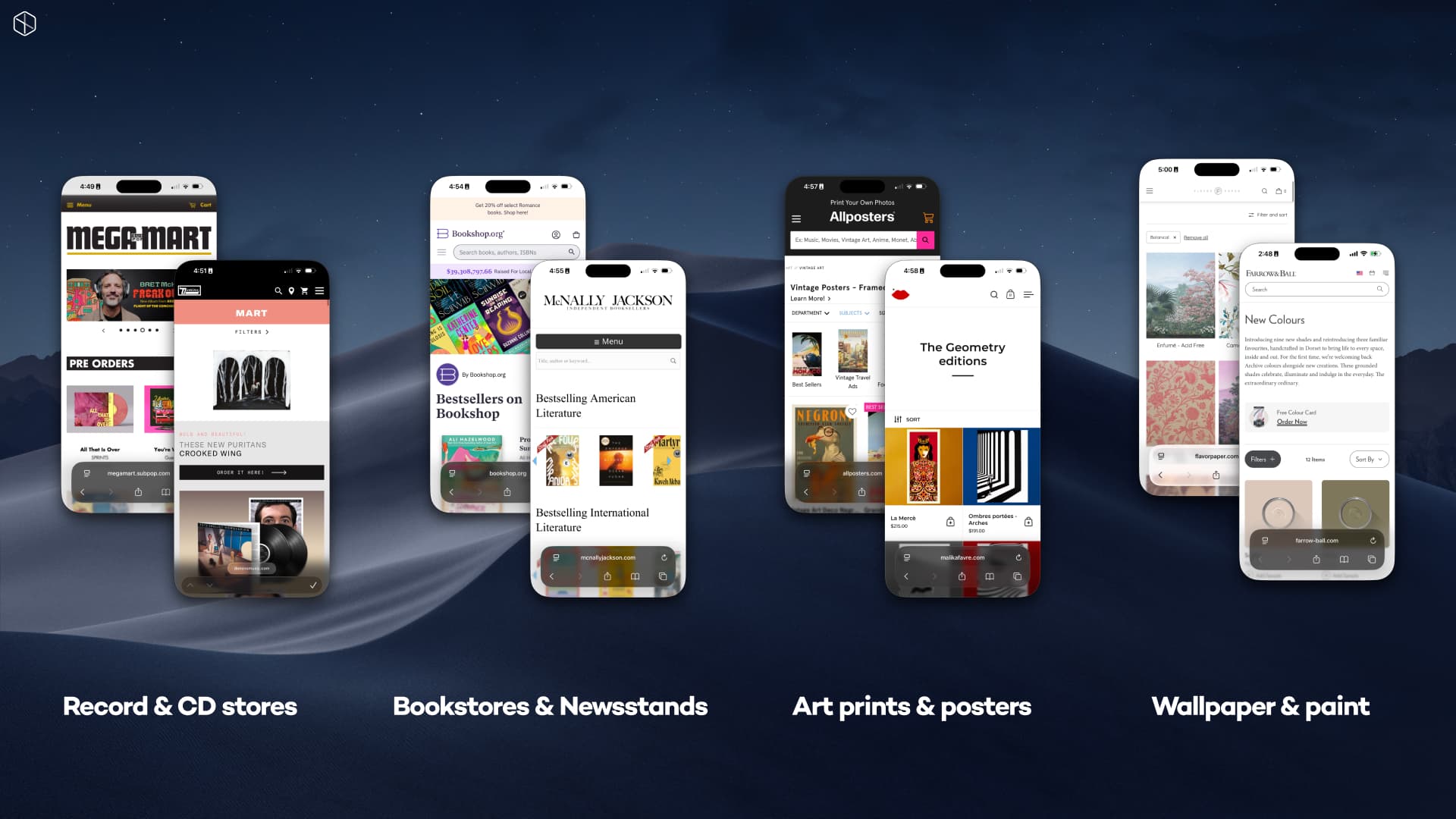

A thorough examination of the kinds of business our target customers operate revealed some really good news: we can easily help present their products, and we wouldn't even have to rely on expensive, unpredictable AI model generation. The products that these businesses sell are frequently ones that aren't embodied in unique objects, but primitives. Reductively, small retailers deal in rectangles: books and magazines, music on CD and vinyl, wallpaper and paint, art prints, stationery. Even with a third dimension—bottles of wine, candles, t-shirts, bedding—geometry is a distant second to the texture applied to it.

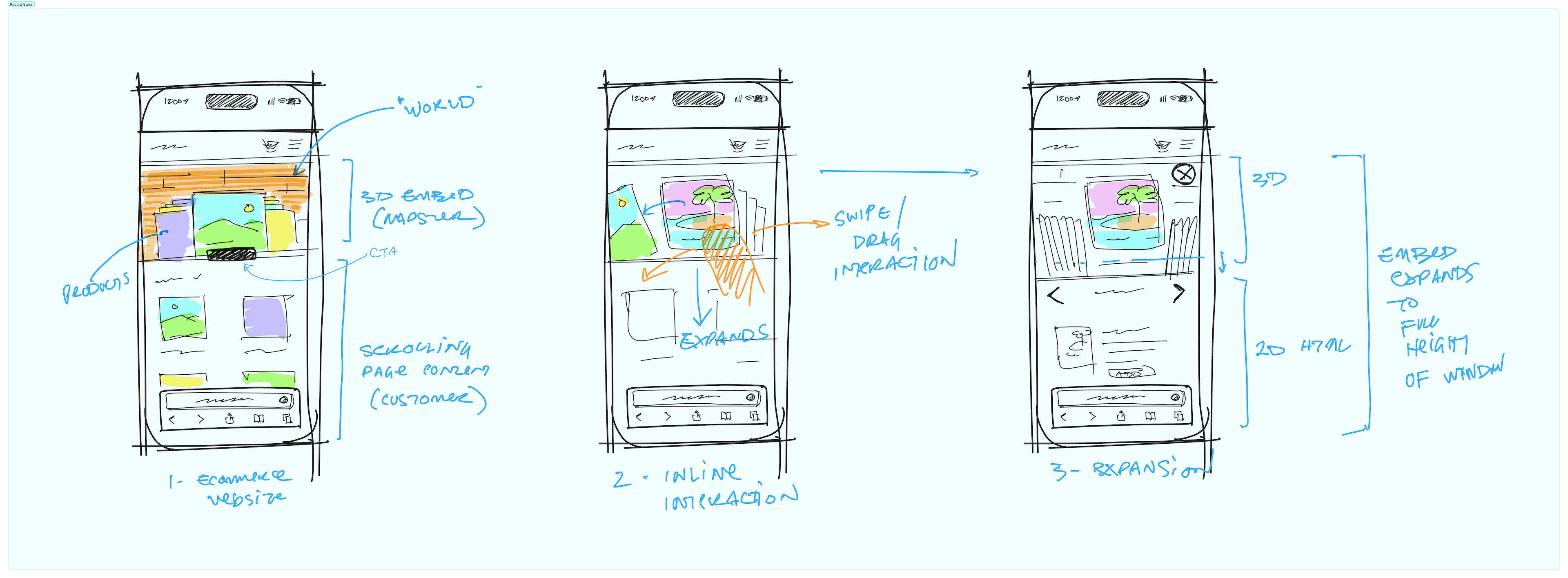

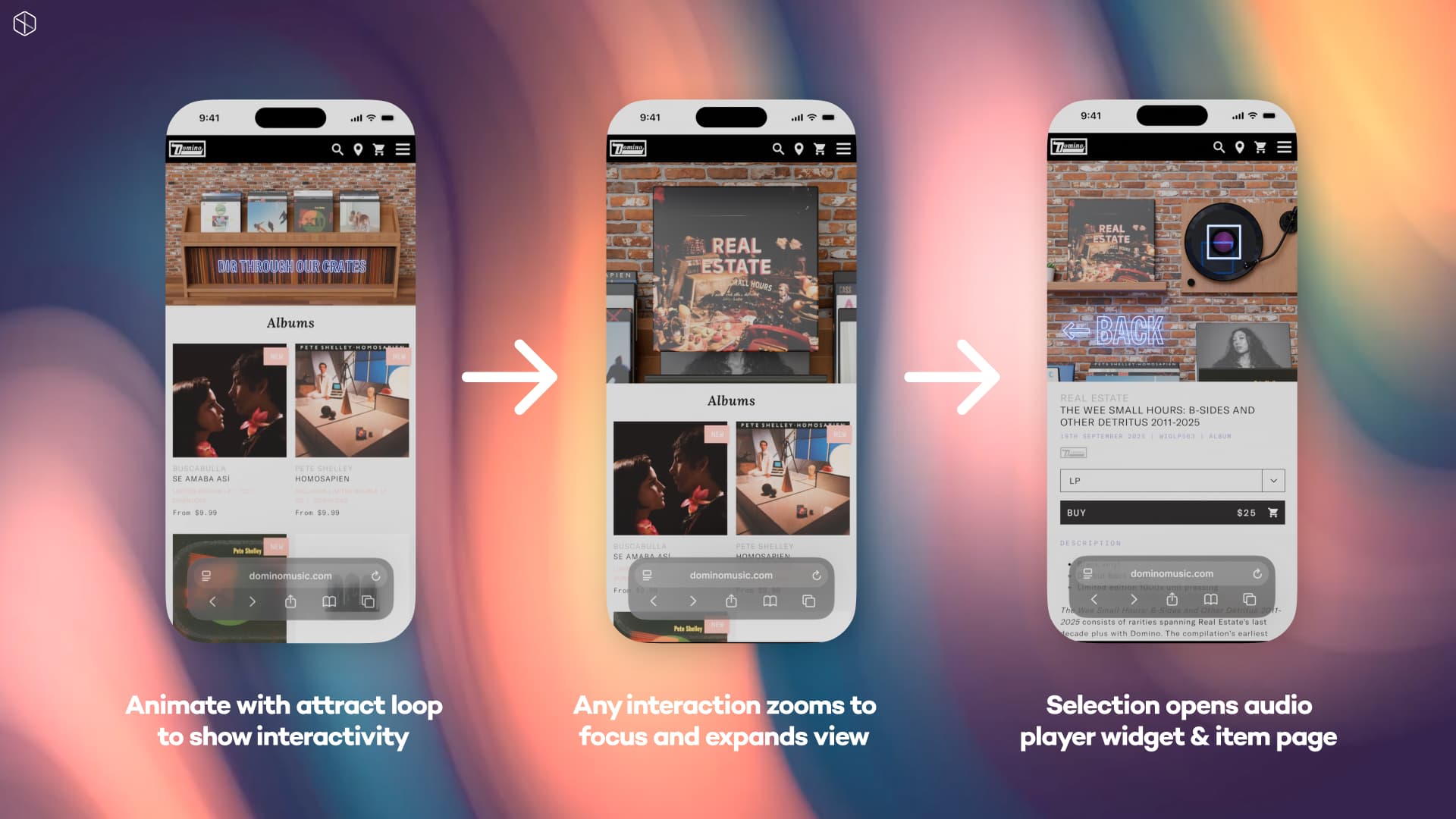

That conclusion was a breakthrough [3] leading to the idea of “Immersive Navigation,” or embeddable enhancements to traditional websites that use spatial interactions with primitive objects to tell a deeper product story. We introduced new forms of Scene, each built with a specific kind of product in mind, with an emphasis on rich, playful interactions populated with content we could count on customers already having on hand. Armed with contextual understanding and integrations with content sources, our AI agent could choose and connect Immersive Navigation Scenes automatically.

Context is for Kings (and Agents)

We knew that AI integration would be a product requirement from the beginning, and the core engineering team was hard at work building an AI agent that worked with our 3D engine. At a time when every product from startups to big tech were throwing an AI chat into the interface, we needed a defter hand here that didn't eclipse our defining feature as an immersive creation tool or waste UI space on something that provided no value. It was important to me that we use AI in a smart way that doesn't have to work hard to justify itself. At the same time, giving AI too much power takes agency away from users and keeps them from learning or building a relationship with the product.

![The initial onboarding page asking 'Share your vision' with a multimodal chat input. A high-fidelity prototype with sample conversation and motion design is linked in footnote [4].](/_next/image?url=%2Fprojects%2Fworld-builder%2Fshare-your-vision.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

The final major inversion behind World Builder was to build an engine for understanding at the core of the creator experience. Instead of asking customers to learn our tool—streamlined though we made it—we opted to spend computational effort into learning the customer. Our new onboarding experience begins with a familiar open-ended multimodal chat willing to accept any input as a starting point [4]. We asked a simple, direct question: Share your vision. Examples on the page connected sample Worlds with the vision behind them, guiding people toward possible starting points for their own project.

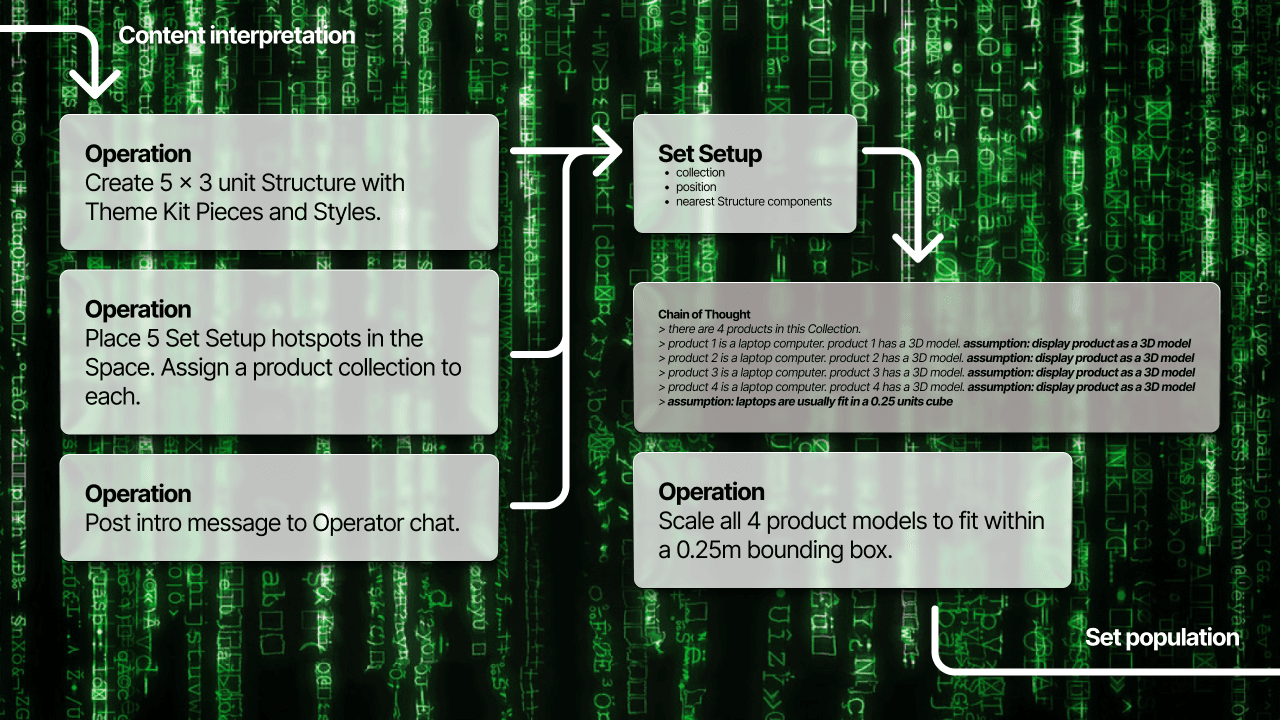

With each input, the agent would ask itself: what can I do with the information we have? It would transparently communicate its reasoning, and provide opportunities for clarification, course correction and reframing. In quick order, we could learn what kind of business the customer had, what they aimed to do, narrow down ideas for Theming and start to figure out what size World to build and what kind of Immersive Navigation patterns made sense to suggest.

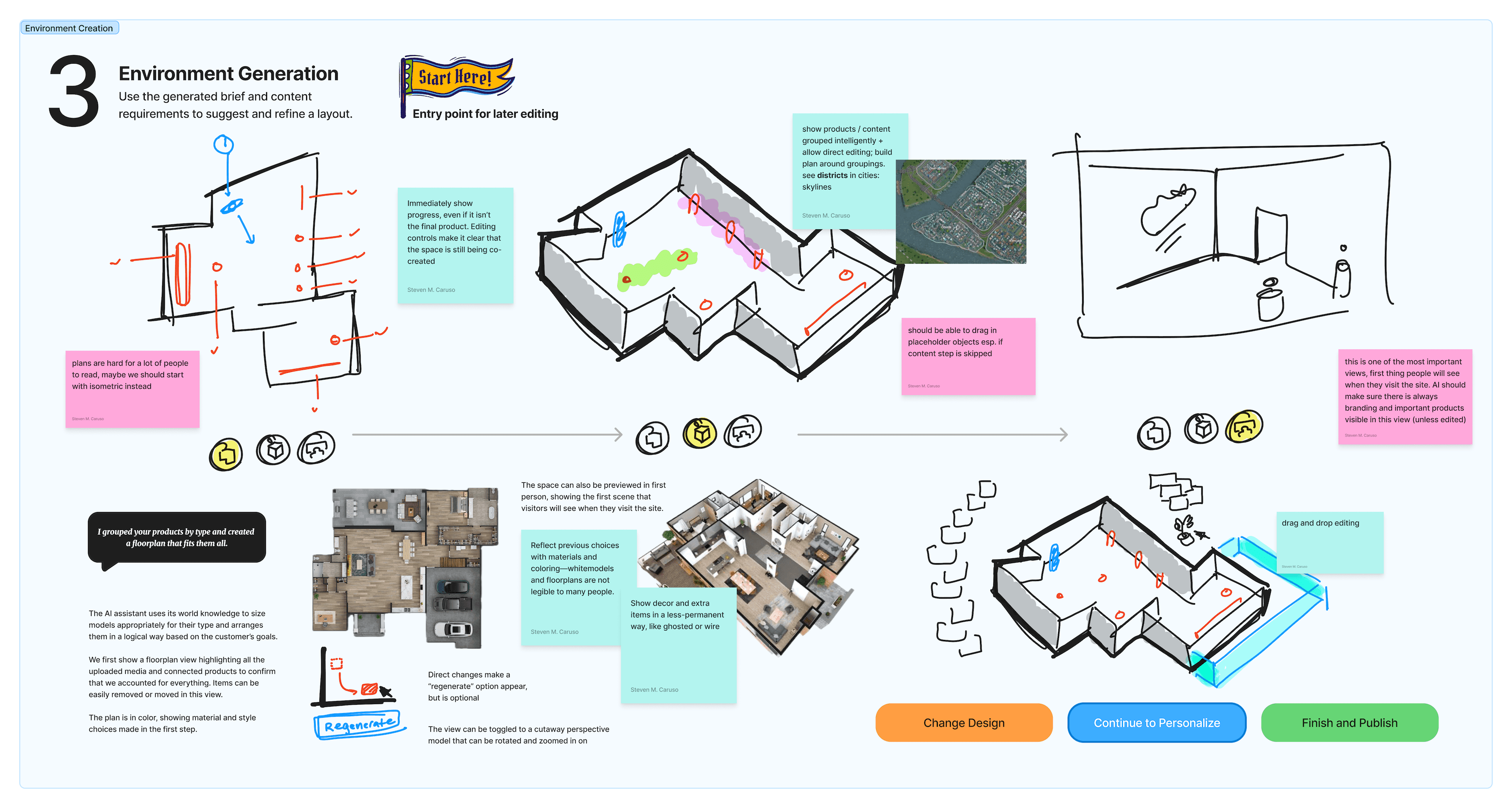

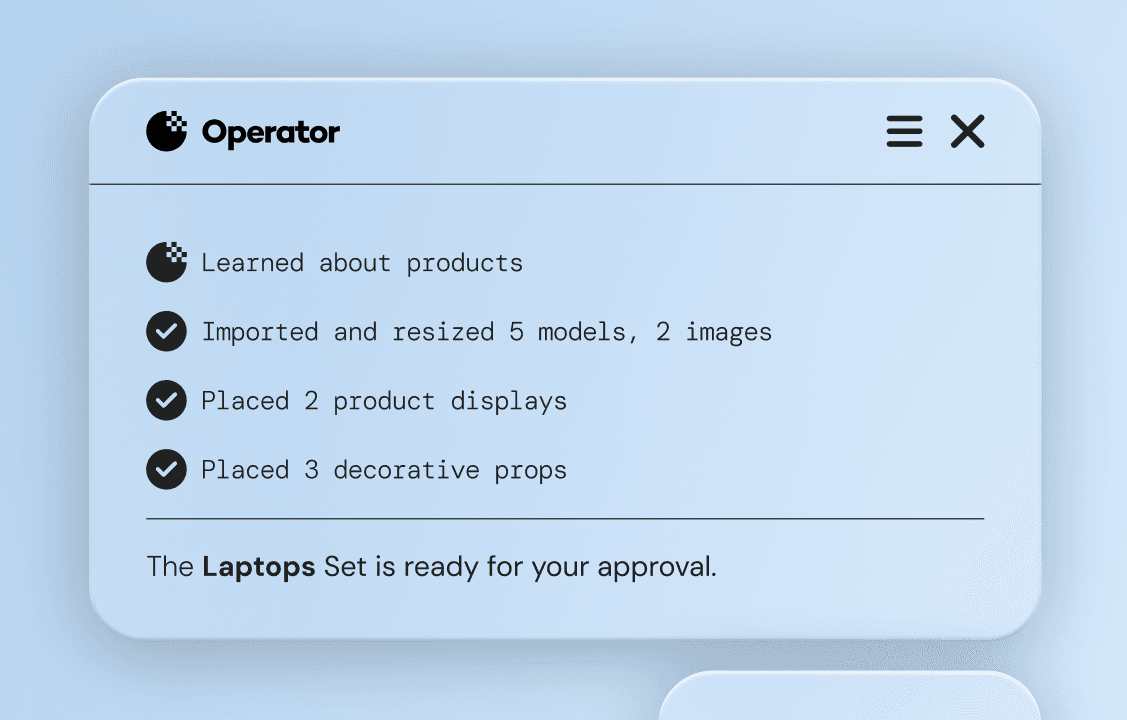

Once we had set the basic parameters of the World, we transitioned from a chat-style interface to a full-page 3D view. With content always as our guiding force, the agent would use it to create a navigational structure for the customer to approve or make changes to. It would then start assembling Sets in sequence, allowing 3D exploration and explaining our process along the way. In this way, we'd show new users how to build with the tool by example—a truly customized tutorial, without relying on contrived placeholders. We'd give people the confidence to go back in and make changes or build new Sets on their own. At all times, though, Operator would be standing by to help.

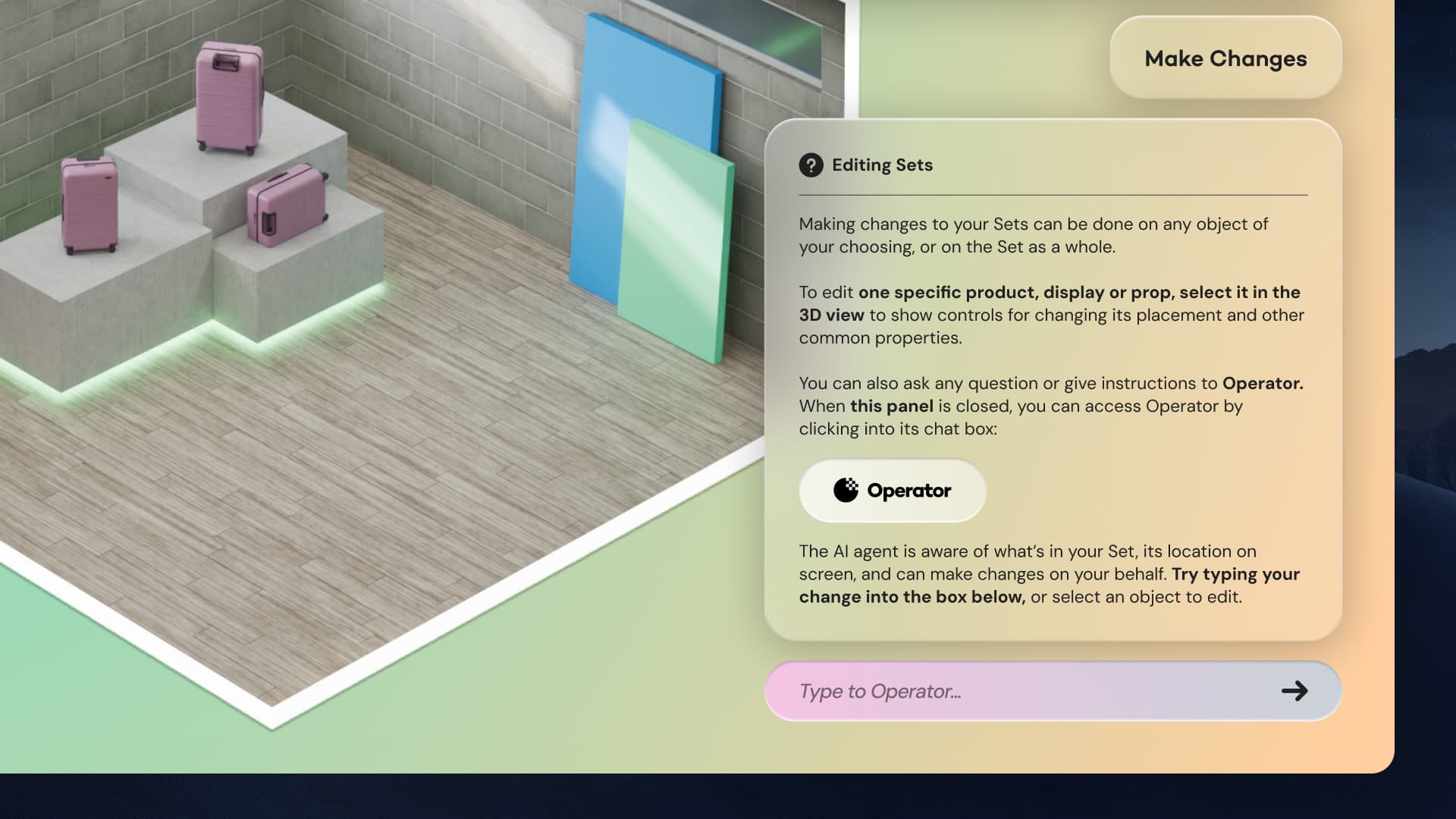

Smooth Operator

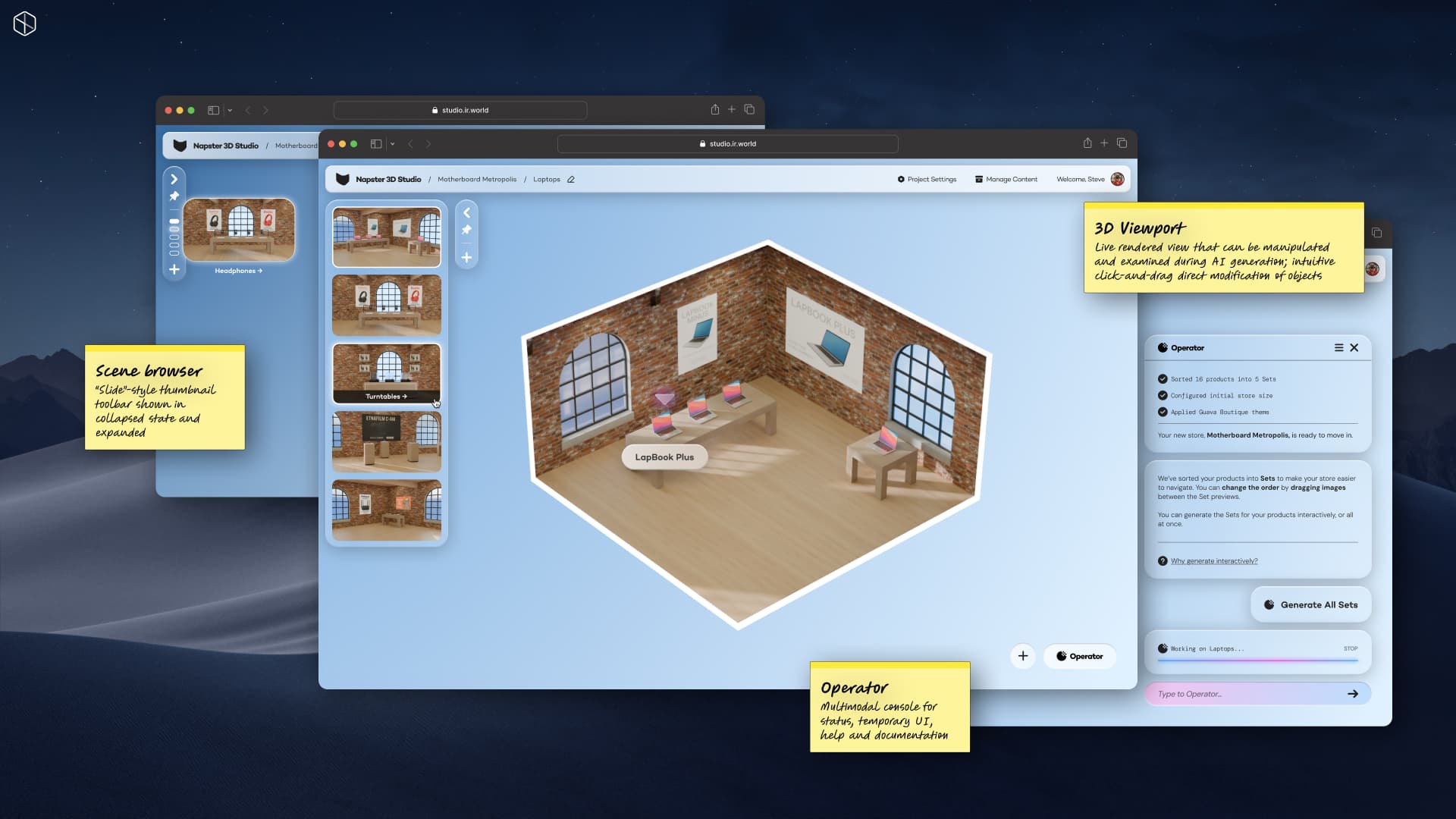

Operator was the embodiment of the AI agent system, with all its functions consolidated into an interface that expands when needed or collapses to put focus on other toolsets. During onboarding, Operator is a full-page experience that then becomes an integrated interface within the 3D editor view. When building and editing Worlds, its functions are threefold:

Its chat history acts as a Status Console that explains what the system is doing at any moment and why.

Responses to text inquiries, 3D view selections and other contextual clues can take the form of focused UI widgets, an Operations Center.

Freeform questions are handled as a Help Desk, surfacing documentation or interactively working through problems.

By keeping Operator visible but unobtrusive, World Builder lets users dip in and out of guidance as needed. The clear hierarchy of Worlds, Sets, Set Pieces and Scenes makes it possible for the agent to assemble complex environments while still giving customers control.

Outcomes & Reflection

World Builder represented a bold rethinking of immersive content creation. By shifting from template-driven environments to a content-first, AI-assisted workflow, the project aimed to make spatial commerce accessible to “Main Street” merchants. The work produced a clear information architecture, a flexible design system, prototypes of conversational onboarding and interactive build processes, and a vision for embedding scenes into existing websites.

Ultimately, strategic priorities shifted and the product was not released in the form described here. However, the exploration yielded valuable insights: 3D experiences for small businesses must start from their content, not ours; automation should empower users rather than remove them from the loop; and AI is most helpful when it explains its reasoning and invites collaboration. These lessons continue to inform my approach to designing tools for the spatial web.